This is a short English introduction to my latest book The Dream of an island. Not yet published in English, but during the fall of 2023 it will appear in German, translated, and published by Ch Beck Verlag.

Just to give the English language readers a preview of the book are here the beginning and the ending of the book – in English, translated by me (I’m sure it is not a perfect translation, but you will at least get a glimpse of the character of my book about islands around the world.

YES. I AM A NOSEPHILE!

It is travel veteran Per J Andersson who presents this confession. He is an incurable island fanatic.

Here we get to accompany him on his journey to ten of his dream islands, such as German Usedom, Spanish El Hierro, Greek Amorgos, Sri Lanka, Denis Island in the Seychelles, Muravandhoo in the Maldivian Raa Atoll and North Sentinel in the Indian Andaman Islands, always at an appropriate distance from sunbeds and umbrella drinks.

Then it’s off to ten of Sweden’s 270,000 islands that the author dreams about at night. They may be tiny and uninhabited, but well worth a visit, such as Blå Jungfrun, Hållö or Häradskär. By the way, did you know that the sea between Stockholm and Turku contains the most islands in the world – 74,000?

But what is it like to be resident on an island? Do you feel isolated or part of a community? In many meetings, we get to meet people who have never left their island or people who have finally found their paradise on earth. Perhaps the magical appeal of islands is ultimately about the longing for places that feel definable, overviewable and safe in times of chaos and uncertainty?

Per is regularly overwhelmed with the longing to travel to yet another island. Preferably one sprinkled with salt and preferably without a bridge connection. In his eyes it is an advantage if the island is inhabited by odd and slightly crazy but at the same time genuine and down-to-earth personalities. The journey there should preferably take some time and not be completely easy. A stormy sea is no obstacle.

“But when I step ashore”, he concludes, “I want to have the feeling of having arrived in a place where life is easy and slow and separated from the complexity of the mainland. My dream of the island hardly makes me unique. It is so common that you could call it banal.”

Because without knowing it, most of us are nesophiles, island lovers. Just check what travel agencies and tour operators offer, and you will realize that the island has a central place in our dreams of another place. Mallorca, also an island, was in the mid-fifties the very first airborne charter destination for many Europeans. The Spanish Mediterranean island is still on the top ten destinations, along with the Canary Islands, Italian Sicily and Sardinia, as well as Greek Corfu, Rhodes and Crete. The Australians, on the other hand, have Bali and the South Sea Islands. The Americans Hawaii and the Caribbean Islands. The Indians Andamans and Maldives. The Japanese Ryukyu Islands. The Chinese Hainan.

Mainlanders like to imagine island life as liberating and transformative. On the islands we therefore feel closest to our origins. We envy the lives of the islanders, who hold so much togetherness with family and local community.

Island dreams from the beginning of time to present day

I am regularly filled with the longing to travel to yet another island. Preferably one sprinkled with salt, preferably without a bridge connection. An advantage is if it is inhabited by odd and slightly crazy but at the same time genuine personalities. The journey there should preferably take some time and not be completely easy. A stormy sea is no obstacle. But when I step ashore, I want to have the feeling of having arrived in a place where life is easy and slow and separated from the complexity of the mainland.

My dream of the island hardly makes me unique. It is so common that you could call it banal. Without knowing it, most of us are nesophiles, island lovers. Just look at the offers of travel agencies and tour operators, and you will realize that the island has a central place in our dreams of another place.

Mallorca, also an island, was in the mid-fifties the very first airborne charter destination for many Europeans. The Spanish Mediterranean island is still on the top ten destinations, along with the Canary Islands, Sicily, and Sardinia, as well as Corfu, Rhodes and Crete. The Australians, on the other hand, have Bali and the Pacific Islands. The Americans Hawaii and the Caribbean Islands. The Indians Andamans and Maldives. The Japanese Ryukyu Islands. The Chinese Hainan.

Mainlanders like to imagine island life as liberating and transformative. On islands we feel closest to our origin. We envy the lives of islanders, who hold so much affinity to family and local community.

At the same time, the island is a place where we as temporary visitors can be at peace. Some of us go so far as to visit islands just to find out who we really are deep down on the inside.

So many imaginations, so many dreams, so many ideas that the islands must shelter. How have they managed to live up to all that we think about them?

The Romans spent their vacations on Capri two thousand years ago, but it was only at the end of the nineteenth century that tourists seriously began to travel to islands. There, in addition to sun, people sought and prayed for origins, the past, and small scale communities, all that has been lost in the industrialized, urban life on the mainland. The islanders were certainly regarded as less educated and civilized than the mainlanders, but on the other hand also as more natural, simpler, more honest and friendlier.

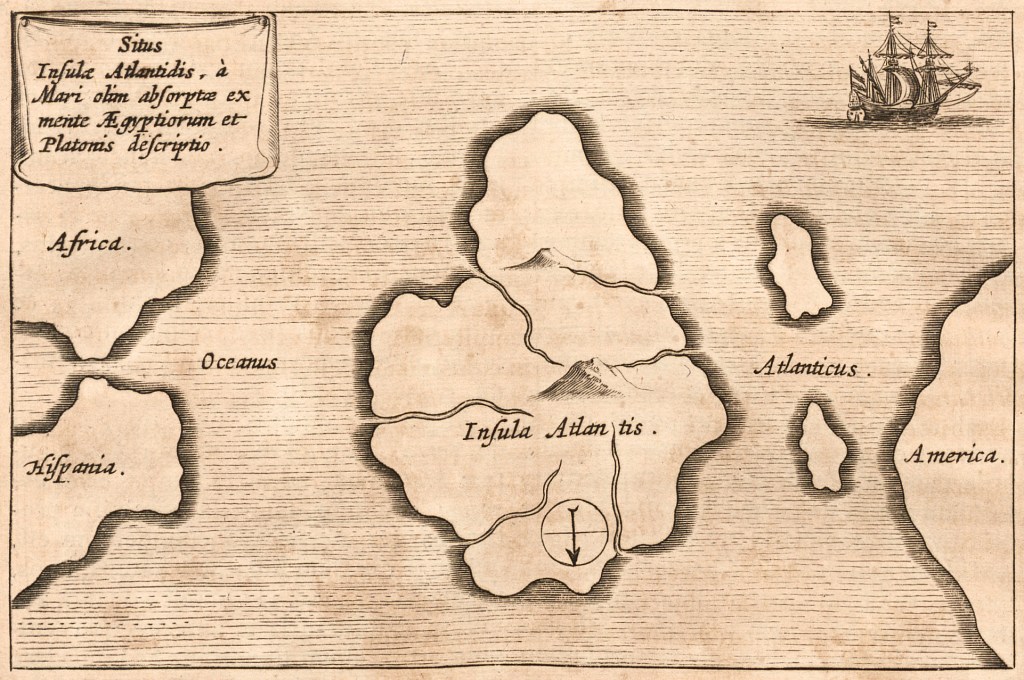

The Greeks in general and Plato in particular saw islands as ideal places to build new cities, both in real life and in the imagination. Plato’s own literary invention, Atlantis, was the image of the perfect island where man lived in paradisiacal harmony. Meanwhile, the islanders were blinded by hubris. After they failed to conquer Athens, their island sank to the bottom of the sea in just one day, which of course was a political allegory of what happens when you ask for too much and break the laws of nature. A warning that is more relevant than ever in the age of global warming where several low-lying islands – such as the Maldives and several others in Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia – are the first victims of rising sea levels. After all, the whole earth is an island in the universe that if we recklessly continue, we risk meeting the same fate as Atlantis.

Although the longing for the islands has a multi-thousand-year history, it is as if the intensity of the dreaming recently has increased. When life feels increasingly stressful and complicated and the world situation darkens, then we dream away to a place where there is peace, simplicity, and harmony. An isolated place surrounded by water that can serve as that ideal world we long for. Of course, the paradise we dream of doesn’t really exist. We know that. But if it should exist, it is most likely be located on an island.

Also in literary history, the island has played a key role in everything from Homer’s Odyssey from 700 BC and Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe from 1721 to William Golding’s Lord of the Flies from 1954.

Golding’s book is about a group of boys who get stranded on an island and start bullying, abusing and eventually murdering each other. The portal idea in the book is that civilization is a thin layer that when scraped off makes us appear as the cruel animals we are deep down. A few years after the book was published, it really happened. A group of boys from Tonga were shipwrecked on a deserted island where they spent a whole year before being rescued. The incident is well documented, including by the Dutch historian Rutger Bregman, who interviewed both the boys (who are now in their seventies) and the crewmen who rescued them. Did it go as in Golding’s book? Did they start forging plots and hacking each other to death? No, says Bregman, noting of that. If you put the real story next to the made-up one, you find out that they are complete opposites. When the boys were found, all were alive and relatively healthy. They had taken care of each other and worked together exemplary to survive.

The idea that isolation on a desert island would bring out the worst in us was put to shame when faced with reality. After all, humans as a species have come as far as we have precisely because of our ability to cooperate. Yet the attitude that man is fundamentally selfish is deeply rooted in Western civilization from Augustine, The Doctor of the Universal Church, via the conservative philosopher Thomas Hobbes to today’s capitalist mainstream culture. It is in the interest of those in power, the Dutch historian believes, to claim that we are selfish monsters. Because if people can’t trust each other and if it’s true that civilization is just a thin layer, then we need kings, CEOs, presidents, bureaucrats, police, military and strict orders and restrictions. In short: then hierarchy is needed.

Yet Alex Garland picks up on William Golding’s thesis in his 1996 bestseller The Beach. In the novel, a group of backpackers in Thailand try to create their own ideal society on an island. The film adaptation of the book was shot in Maya Bay in Thailand’s Kho Phi Phi. After the premiere, the island was flooded with travellers who wanted to experience the paradisiacal settings of the film. But the tourists found only overexploitation and overcrowding. The travellers in the book who try to establish the perfect society fail, because Alex Garland (like Golding) seems to believe that even the pleasant experience of a perfect tropical beach cannot stop human selfishness, envy and lust for power.

The dream of the island is not new. Before we knew how to travel the world’s oceans, we fantasized about doing it. The map that represented the world beyond the horizon wasn’t empty just because we hadn’t been there. With the help of imagination, the oceans were very much alive even before we mapped them. The mythological geography of imaginatively drawn islands and sea monsters was at least as real to medieval people as the real world that eventually replaced the invented. In those days, myth and reality were happy to flow together. In medieval world one did not draw a sharp line between the two perceptions as we do today.

Therefore, the first round-the-world voyagers did not expect to experience something unknown on the distant islands, but something that was already known thanks to fairy tales and myths handed down since ancient times. They saw it as rediscovering the islands that had been written and talked about and drawn on maps for a thousand years. The first challenge when they stepped ashore on islands in the Atlantic and the Caribbean was therefore to free themselves from their preconceived notions and replace them with actual observations. It must have come as a shock to them.

I think the explorers, given their vivid imaginations, could have stayed home and continued to dream. One who did so much later was Judith Schalansky, the German writer who thought about and longed for islands all her life. Because she was born on the wrong side of the Berlin Wall, as a young person she could only travel in her imagination. In the book Atlas of Remote Islands: Fifty Islands I Have Not Visited and Never Will, from 2009, she takes us to places that, like the sailors of the Middle Ages, she filled with invented life. The book became an international bestseller. So strong are our island dreams that we are prepared to devour both real and fictional island descriptions.

Perhaps it would be better if I did like Judith Schalansky and let the dreams of adventure, exotic cultures and ideal island communities remain dreams?

To understand the idea history of the islands, I read the American historian John R Gillis Islands of the Mind – How the Human Imagination Created the Atlantic World, one of the most ambitious attempts made to understand the role that the islands played in Western thinking.

Gillis teaches me that in the early Middle Ages the Garden of Eden, the earthly paradise, was placed on tops of mountains, because it was thought that the mountains were a step closer to the kingdom of heaven and had escaped the deluge that drowned the lowlands. For example, in Divina Commedia from 1321, Dante Alighieri placed paradise at the top of Mount Purgatory. Some scholars have proposed a real model for the Garden, suggesting that it is either located somewhere in Armenia or at the mouth of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers in the Persian Gulf.

When the Ottoman Empire in the fourteenth century blocked the land route to the east and the Europeans instead set out to the western seas, paradise was moved from the mountain tops to the islands. The Portuguese and Spanish were convinced that they would find the Garden of Eden on islands and group of islands that eventually came to be called Madeira, Canary Islands, Cape Verde and Azores. When they discovered that the islands were not as paradisiacal as they imagined, they instead began to see them as places where one could make a worldly fortune. As competition for land and resources had increased in mainland Europe, it seemed easier to get rich on the sparsely populated or uninhabited islands. The primitive savages who possibly already lived there were easily subjugated.

Those who first sailed further west imagined the sea to be full of islands. So strong was this obsession that it took a long time before they realized that some of the land masses, they came to were not islands but in fact continents. Christopher Columbus was one of them. He did not imagine that he would sail across vast expanses of sea, but through a dense archipelago of thousands of islands. Once he found America, he was so obsessed with the idea that he lived his whole life believing that the New World was not a continent, but an archipelago.

Columbus was also convinced of having rediscovered some islands mentioned in the Bible. When he anchored off Hispaniola, which today is shared between the Dominican Republic and Haiti, he thought he had found the mythical islands mentioned in the Old Testament, including Ophir, where King Solomon sent ships to fetch gold, sandalwood and precious stones. Columbus was convinced that he had found one of the biblical islands and thus brought humanity one step closer to the Second Coming of Christ. Now, he thought, the earth could become whole again and the seas disappear. ”He [Columbus] placed himself at the centre of the divine drama and gave the islands the important role they had in the Bible,” writes Gillis. What a hubris!

Since the Spanish conquistadors had seen the treasures of the Inca Empire, the sailors were also looking for the gilded city of El Dorado. The gold-covered walls of the temples kicked off the dreams of an entire city, an entire mountain, an entire lake or an entire island covered in gold. Hernán Cortés also searched the sea between South America and the Moluccas, as did Álvaro de Mendaña who scouted for the island where, according to the Old Testament, King Solomon got his gold. Consequently, the islands Mendaña found are now called the Solomon Islands.

In ancient Greece there was the myth of the Fortunate Isles, the imaginary islands also known as Isle of the Blessed, located somewhere in the western Mediterranean. On them was a worldly paradise inhabited by incarnations of the superheroes of Greek legends. The philosopher Plutarch, who believed that they lay some distance out into the Atlantic, described them as the place where the air is always balmy, where the rain is like silvery dew, and where the happy inhabitants without effort can eat their fill of ripe fruits.

In the twelfth century, the dream islands multiplied. Saint Brendan was now plotted on the charts somewhere west of North Africa and a monk who claimed to have been there reported an “Atlantic paradise”. A hundred years later, another island appeared on the maps. Brasil or Hy-Brasil, they called it and placed it west of Ireland. The fact that no one saw it with their own eyes mattered less.

Until the fourteenth century, one could say that the seas led nowhere. After that, they led everywhere. In the four hundred years that followed the expeditions of Columbus, Vasco da Gama, Amerigo Vespucci, Ferdinand Magellan, the era Gillis calls the Age of islands, the Europeans found more dream islands. On the one hand, paradisiacal islands that had everything that man had lost through the fall of sin – in other words, places that no longer existed – and on the other hand, utopian islands that stood for the hopes of a better social and political system than the existing ones – that is, places that not yet existed.

The islands became objects of political visions of societies that were more human, democratic, equal and happy. In 1516, Thomas More was the first to publish the book Utopia, which is about an island where life is so much more beautiful and better than back home in England. He constructed the name of the island from the Greek words for not and place, meaning nowhere or a place that does not exist and that is too good to be true. Despite the revealing title, it is written in such a way that one is led to believe that the island really exists. At the beginning of the story More meets a Portuguese skipper in Antwerp who has been on one of Amerigo Vespucci’s expeditions to the New World. There they disembarked on the island of Utopia, says the Portuguese, adding that he lived for five years on the island, which is the antithesis of England. All property is shared, there is full employment, a six-hour workday, and job rotation (two years of his life every townsman must work in agriculture). Hunting and slaughtering are considered barbaric pursuits. There are no conflicts between the residents and therefore no lawyers. If there is a war with other islands, you hire mercenaries from the belligerent neighbouring states or you bribe your way out of the problem. For the Utopians, peace and not war is the most glorious thing. Gold and precious stones have no practical use and are therefore worthless and nothing to strive for. Each household consists of collectives of at least forty people who are related to each other. Those who mock and make fun of others are considered strange and deviant.

In other words, a relaxed, peaceful, vegan people who live in collectives, lack the need to assert themselves and treat their fellow humans with respect. Could it be better? More was probably inspired by Vespucci’s real-life travelogue from North America where the Italian navigator describes the natives of the Caribbean islands with the words: “They have no private property, everything is shared. They live without a king, without authority, each is his own master.”

Just over a hundred years later, it was time for another book about the ideal dream island. Francis Bacon came up with The New Atlantis in 1626, influenced by both More’s Utopia and Plato’s description of the sunken island. Bacon’s story begins with a European ship en route from Peru to China and Japan being driven astray by storms. After a long time at sea, the supplies run out at the same time as more and more people on board fall ill. Then they finally aim for an island in an unknown part of the Pacific Ocean. When they have stepped ashore, they are accommodated in the ”Foreigners’ House”. The sick get medicine and recover. When they talk to the islanders, they realize that they have arrived at an ideal society. They are welcome to stay on the island if they wish. The island is called Bensalem, a name composed of the Hebrew ben which means son and salem which stands for whole. The islanders tell us that they have a king named Solamona, reminiscent of the Old Testament’s Solomon. In the past, there was a lively and profitable trade with the rest of the world. But to avoid the harmful influence of evil, the king chose to isolate the island. Centuries passed, world trade declined, and navigation skills were forgotten.

In 1602, the Italian philosopher Tommaso Campanella’s book The City of the Sun, was published. The frame story is a conversation that is said to have taken place in an Italian port city a hundred years earlier. A sailor tells a man in the harbor how, during a round-the-world voyage, he came ashore on the island of Taprobana, which was the ancient Greek name for the island that is today called Sri Lanka. On the island, the sailor tells us, there is a fortified and impregnable city surrounded by a ring wall and divided into seven circles within each other. Each circuit is surrounded by a wall. Residents can move from one circuit to another through different gates. In the middle of the innermost circle is a temple with an altar with two globes, a celestial globe and a terrestrial globe. The state of the sun is led by an elected high priest and has three advisers called Power, Wisdom and Love. Every other week there is a big meeting where everyone from twenty years and up, both men and women, can participate and have their say – and even depose the officials if they feel like it.

But the islanders don’t have that much freedom. The leaders decide who will mate with whom and exactly when they will have sex so that the offspring will be optimal. The timing of sexual intercourse is determined by how the zodiac signs stand in the sky. The children stay with their mothers until they are two years old and are then brought up under joint auspices. All property is shared, and the leaders distribute supplies as needed. Science and technology are highly valued, and it is considered more important to study nature with one’s own observations than to memorize book knowledge. The religion, finally, is a syncretic amalgamation of the best of Christianity, astrology and other Eastern teachings.

In 1656 it was time for more island fantasies by Europeans. Then James Harrington’s The Commonwealth of Oceana was published, which was about an island where power cannot be inherited as in the European monarchies but must rotate between different social groups via democratic elections. Nor should anyone be allowed to own too much agricultural land it should instead be distributed fairly.

The wave of books about dream islands was an effect of traded tales rooted in the ancient world and the affliction for islands among European sailors and explorers in the centuries after Columbus. The dreams were reinforced by the colonialists’ depictions of the happy life the lush Caribbean and the Polynesian islands where the population was described as happy natural people who indulged in erotic debauchery and irresponsible pleasures in a nature rich in fruit with unlimited lust.

As Lord Byron wrote in the poem suite The Island from 1823:

The white man landed!—need the rest be told?

The New World stretched its dusk hand to the Old

Kind was the welcome of the sun-born sires,

And kinder still their daughters’ gentler fires.

Their union grew: the children of the storm

Found beauty linked with many a dusky form

The Cava feast, the Yam, the Cocoa’s root,

Which bears at once the cup, and milk, and fruit;

The Bread-tree, which, without the ploughshare, yields

The unreaped harvest of unfurrowed fields,

The magical appeal of the islands is ultimately, I think, about the longing in a chaotic and uncertain world for places that feel definable, over viewable, comprehensible and safe. The question is whether there is any dream that is more universal.

But do all people on earth dream of islands equally? American Chinese geographer Yi-Fu Tuan is sceptical. He believes that the island certainly has a certain universal appeal, but that this is still strongest in the west.

John R Gillis believes that there is – or was – also a class aspect. Historically, Europe’s poor have not dreamed of ideally organized societies on remote islands, but rather of the heavenly kingdom that, according to the Book of Revelation, will one day appear to the faithful. Neither nomad people like the Sami and the Romani, nor the tinkers and the tramps have had so many island dreams, because they are constantly on the road themselves and know better than to fantasize about paradise beyond the horizon – or behind the next road bend or in the next valley. Not even in centralized and powerful states such as the Roman Empire, Imperial China or later the Soviet Union did the dream of the paradise island thrive, Gillis believes, because the citizens of the empires were indoctrinated to believe that they were already in the middle of it.

The Chagos Islands pique my curiosity. In the early 1970s, the British sent away the last indigenous people from the island group officially called the British Indian Ocean Territory, located just south of the Maldives and home to a British-American military base. The Chagossians have long dreamed of returning to their home islands. So at the beginning of 2022, a group of lucky natives who lived in exile in Mauritius were allowed to return for the first time. Ideally, they want the British to leave so they can have the islands for themselves. They have received support for this in both the UN and several international courts. But the British refuse. The islands have too great military strategic importance. In 2021, Mauritius turned to Wikipedia to remove the information that the islands belong to Great Britain. With some success, for now it says: “[In 2019 Chagos Islands] was recognized as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage from Mauritius. In January 2021, the United Nations General Assembly approved a resolution proclaiming this. In 2021, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea confirmed for its jurisdiction that the UK has ’no sovereignty over the Chagos Islands’ thus the islands should be handed back to Mauritius”

Chagos are examples of islands that most mainlanders have never heard of. There are, of course, more unknown archipelagos. Raise your hand if you can dot the Queen Elizabeth Islands, the Lackadives and the Nickobars on a world map! No, thought so! Thus, the whole world is not mapped in the sense that it is generally known to a large number of people. If there are places we’ve never heard of, they’re most likely remote islands.

The era of colonial acquisitions is over. Instead, the tourists have assumed the role of colonizers. Today, we travel to islands in search of, in Gillis’s words, “grand seclusion and an atmosphere of timelessness,” in short, everything that the early explorers sought. And, one must add, the isolation that more and more people living permanently on the islands are struggling to escape.

Like any other central metaphor, the island can represent a variety of things. The islands evoke so many conflicting desires, fears and desires. They can stand for exposure and vulnerability but also wholeness, authenticity and security. Islands represent something we have lost and are thus a place where we can recover. They are metaphors for paradises and hells. They are both attractive and repulsive. They represent both separation and continuity, isolation and connection. They make us look into the past and into the future. We project our desires and our cravings onto them. At the same time, they are useful as places where we can express our greatest fears. Just to take a few examples, as in Arnold Böcklin’s painting Isle of the dead from 1880-1881, Stephen Spielberg’s film Jurassic Park from 1993 and the six seasons of the American television series Lost that was aired between 2004 and 2010.

We can feel unusually free on islands, but also extremely confined. Although islands are nowadays most often associated with fun, peacefulness, and relaxation, not least in the tourism industry, they still represent pain. To the islands we send subversives, criminal immigrants, asylum seekers, the infected and other undesirables. Napoleon Bonaparte was forced to go into exile on first Elba and then Saint Helena. The French later sent criminals and regime critics (including Dreyfus) to Devil’s Island just off French Guiana, the British shipped their thieves and state enemies to Australia, the Seychelles and the Andaman Islands, and South Africa locked up apartheid opponents like Nelson Mandela on Robben Island. Venice sent lepers to the island of Lazaretto and plague infected to Poveglia, while Sweden isolated the infected on Känsö in the Gothenburg archipelago and Fejan in the Stockholm archipelago. Recently Australia sent asylum seekers to Papua New Guinea and Nauru to avoid having them on their own giant island which is more of a continent.

On islands in the Caribbean and Indian Ocean, the British and French established plantations where the work was done by slaves. For them, of course, the islands were synonymous with coercion, violence, death, and disease. As hopeful as island life seemed to the dreamy colonialists, it could be as hopeless to the subordinate and colonized.

During the Enlightenment, scientists turned the island into a kind of nature’s own laboratory. Anthropologists saw them as ideal for field studies in indigenous cultures. The foundations of today’s social anthropology were laid by Bronislaw Malinowski’s field studies on an island, specifically Kiriwina in the Trobriand Islands.

In short, Europeans were fixated on islands on which they projected their dreams, marvelled at and emigrated to – and of course also got rich on, explored their origins on and felt reborn on.

The Indian and Chinese mainland empires, which dominated the world economy before European colonialism, on the other hand, continued to look inward towards the center of the continents. Indian kingdoms had their centres far from the coasts and saw the sea – which was called kala pani, the black waters – as both threatening and impregnable. In China, where, after several attempts, they gave up getting rich on long-distance shipping, they were so amazed that in a guide from 1701 they grouped together all the Europeans, Americans and Africans who they thought was obsessed with seas and islands and called them “the people of the great western sea”.

Throughout the colonial era, the islands evoked our desire to be rich, and to rule. At the same time, they were reminders of powerlessness. In other words, the islands arouse both stronger hopes and darker feelings than any other form of landmass. In the Disney film Moana from 2016, we get to go along to the green island of Motunui located in a sparkling sea. Coconuts fall from the palm trees, the grass grows healthy, green, and soft, the foliage is lush and the flowers many and colourful. On the island you see baskets full of fresh fish and trees and bushes teeming with bananas and taro fruits. The islanders are industrious, relaxed, generous, collective, happy, joking and dancing. The message couldn’t be clearer: Motunui is paradise. After its premiere, the film sparked debate at universities in the United States, Australia and New Zealand and was accused of cultural appropriation of Pacific Island culture. But when it was shown to students at the National University in the island nation of Samoa to spark a discussion about cultural theft, it was met with the opposite reaction, Kalissa Alexeyeff and Siobhan McDonnell say in an essay in the journal The Contemporary Pacific. The students on the Pacific island felt that Moana should be praised for portraying island life so beautifully. The film, they said, made them proud to come from a place that inspires such a paradisiacal depiction.

In Western cosmology, water stands for chaos and land for order, while the islands are a third kind of place. Something between land and sea. Islands therefore work well as gateways between the two worlds and to another kind of life.

In ancient Greece, people saw themselves as inhabitants of a world that was itself an island. A land mass surrounded by water. Not a bad guess, because that’s exactly what all the continents are, including Eurasia to which Greece belongs. The water that surrounded us defined the world. In both ancient Greek and Middle Eastern mythology, the beginning was imagined as a chaos consisting only of water. In the Old Norse societies, it was believed that the earth was an island in the ocean where a huge serpent and other sea monsters lived. The Hebrews imagined the sea as a primordial chaos from which God, with his wisdom, succeeded in creating the earth and thus also man.

Both in ancient Egypt and India, they worshiped the water in streams, creeks, rivers and lakes, but had a strong feeling of distaste for the sea, which they preferred to stay away from. The Greek heroes were also sceptical. When you set off for the islands, you always had the stated goal of sooner or later returning to the mainland.

Voyages to sea were fraught with danger and therefore a strictly male occupation. Decent women like Penelope in Homer’s Odyssey remained on the home island when the men left, while seductive women like Circe and the Sirens were out on the islands, ready to tempt and destroy the sex-starved sailors. The fondness for islands, Gillis believes, is thus a legacy from ancient Greece that has been propagated through the era of the great discoveries and into our time.

For man, water has been the source of life, but at the same time its destroyer. The fear of flooding was ever-present and has been passed down. Today, rising sea levels as an effect of climate change are even the image of the imminent demise of our modern civilization.

The globetrotters’ search for island paradise was strongly sexually charged. Alongside the purely economic allure of the global spice trade was the erotic desire. The European navigators, all of whom were men, were obsessed with the possibility of landing on islands that were imagined as round and seductive. The New World was considered feminine, while undiscovered islands were often described as “virgin”. Columbus is even said to have defined paradise as an island in the South American Orinoco Delta that was shaped like a woman’s nipple.

But there were also notions and dreams of islands where women rule. In medieval Japanese mythmaking, the island of Yonaguni was called the Island of Women because it was believed to be inhabited only by women. Men who came to visit were served delicious meals and in return were expected to have sex with as many of the island’s women as possible to ensure regrowth. If boys were born, they were killed immediately, while the girls were raised to be strong, independent women who were expected to carry on the traditions.

The Swedish artist Tyra Kleen had similar fantasies as a little girl at the end of the nineteenth century. She dreamed that as an adult she would travel to an uninhabited tropical island, the kind Robinson Crusoe washed ashore on. There she would give birth to twelve children. They would grow up naked, free, and happy. The children’s father would be a shadowy figure, just as her own father had been. In her diary entries, she wrote that the father would disappear ”much like the drone of the bee society when he has fulfilled his mission”, i.e. fertilized the female and ensured the survival of the species. Left on the deserted island, she and the children would live in a utopian matriarchy. She drew and painted many pictures that embodied her dreams of the island with only women and children.

Sometime in the late nineteenth century, the world’s islands were finally explored and plotted on maps where they had to replace fantastic sea monsters, giant sea serpents and dreamlike fantasy islands. The time of great discoveries was over.

Still, the island hunt did not end. Because then the dream of the paradise island was taken over by the tourism industry. A quick google gives a selection of headlines in travel catalogues, travel magazines and on the travel pages of daily newspapers:

Beautiful paradise islands around the world

5 paradise islands that don’t cost a fortune to visit

10 paradise islands you must visit before you die

Find your own paradise island in the Maldives

5 lovely paradises in turquoise and white

Here are the South Sea’s 9 most delicious paradise islands.

Many of today’s vacationers, including tax evading westerners and Russian oligarchs with their luxury yachts, who, like the explorers of old times, searched in vain for the island paradise.

But before I go, I’m not afraid to be disappointed. For my conviction is strong: Paradise is forever lost. The paradise island never existed. From the sea, however, I hear a faint but seductive voice whispering that I shouldn’t be so sure. You won’t know until you look for yourself, the voice whispers.

So that’s why I’m leaving for the islands.

This introduction is followed by ten chapters on ten islands, namely El Hierro, Northern Sentinel, Bal, Gotland, Denis Island, Sri Lanka, Usedom, Norrbyskär, Muravandhoo and Amorgos. Written with a mixture of essays and travel reports, with a strong sense of presence.

The country with the most islands in the world

267,570 islands. No other country has as many. It is hard to imagine that they can be so numerous, even for a Swede like me who lives on one of them and often vacations on another of them.

After Sweden in the top ten in the list of the countries with most islands come Norway, Finland, Canada, and the USA. One explanation for the large number of islands here in the northern hemisphere is the last ice age, which ended ten thousand years ago. The four-kilometer-thick ice masses pushed down the northern landmass – in North America down to the Great Lakes and New York, in Europe down to central Great Britain and northern Germany. Since then, the elastic crust rises slowly but surely. The further north, the more land elevation. In the Bothnian Sea – the northernmost part of the Baltic Sea – the land rise is one centimeter a year, while in southern Sweden it is only a modest one millimeter. This means that the land in the north has risen by several hundred meters since the ice melted – and will rise by at least another thirty meters before it is finished. My son, who studies geosciences, has calculated that in our part of the world land is rising faster than sea level rises caused by climate change. On the island in Stockholm where I live, no one therefore needs to worry about being flooded – unlike the inhabitants of the low-lying islands in the Indian Ocean and the Pacific.

For the last ten thousand years, the number of islands in the Nordic countries has been constantly increasing as underwater rocks slowly rose out of the sea and became visible above the surface. In the next ten thousand years, more islands will be formed in this way. On the other hand, many islands disappear when the narrow and shallow straits between neighboring islands and between islands and the mainland rise and turning them into fewer but larger islands and into peninsulas.

However, most of the islands are not worth even thinking about, much less visiting. Because just over nine out of ten Swedish islands are less than ten thousand square meters. Many of them are nothing more than a few treeless rocks where seabirds’ nest.

In Sweden, most of the inhabited islands are in the Stockholm and Gothenburg and Bohuslän archipelagos. Here, many of the islands, on the other hand, are extremely densely populated.

Could it be true? you think and think of salt-sprinkled small islands far out in the ocean. Yes, it can! One in six inhabitants of Sweden, i.e. 1.6 million people, lives on an island that is either in the middle of or near a city. Statistics Sweden (SCB), from which the figures come, also includes Stockholm islands such as Södermalm, Kungsholmen and Essinge Islands and the Gothenburg Island Hisingen. In Stockholm, the whole of Södertörn and Värmdön are also classified as islands, which no one who lives there does, because the straits that separate them from the mainland are so narrow that you hardly think of them when you cross the short bridges.

In any case, it means that more than half of the inhabitants of Stockholm County are counted as islanders. Even if the people who live there hardly perceive themselves as such.

I live on the world’s thirty-fourth most densely populated island, namely Södermalm in the central part of the Swedish capital. Like practically everyone else who lives there, I don’t consider myself an islander either. Perhaps because the island has a total of thirteen bridges connecting it to other islands around which in turn have bridges connecting them to the mainland. In addition, the bridges are short, so narrow that you easily forget that you are on a bridge at all. We can therefore overlook the densely populated city islands when it comes to specifically island characteristics.

Nevertheless, the densely populated islands are the exception that confirms the rule. Most of Sweden’s islands do not have a single house. On only eight thousand of Sweden’s islands, i.e. only three percent, you can see some form of building when you step ashore. In Swedish, we often call the very smallest islands something else. We say grynna (about rocks that hide just below the surface of the water but sometimes show above), rev (about elongated underwater beds or protruding banks built up by sediment), skär (about above-water rocks), kobbe (about small low, round islands a little further into the archipelago) and holme (about small and uninhabited islands), which tell us that most of Stockholm’s many islands were uninhabited when the name was coined.

What is an island?

The short definition of an island, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica, is a piece of land surrounded by water, smaller in surface area than a continent, located in seas, lakes, or rivers. The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea means that a place that wants to call itself an island must also have some part that is above the water’s surface, regardless of the tide level. Africa-Eurasia, America, Antarctica, and Australia are surrounded by water, but stand on their own tectonic plates and are therefore counted as continents. In addition, they are therefore far too large for us to think of them as islands.

In the case of sea islands, geologists distinguish between continental islands that lie on the same continental shelf as the mainland and oceanic islands that lie by themselves further out.

Continental islands usually have a geological structure consistent with the adjacent continent or have been formed from sand and other sediment carried by rivers into the sea. Gotland, Usedom, Bali, Sri Lanka, Norrbyskär and Amorgos are continental islands.

Oceanic islands, which are thus outside the continental shelves, have often been formed after volcanic eruptions or from calcareous structures from the skeletons of coral animals. El Hierro, North Sentinel, Denis Island and Muravandhoo are oceanic islands.

If you are interested to buy the rights to publish it in English or any other language except Swedish and German, place contact my agent Gudrun Hebel in Berlin at Agentur Literatur. Tel. +49 30 347 077 67, email info@agentur-literatur.de. You can also contact me, the author, on per@vagabond.se.